The bell of the omnibus circuit phone rang just the once. That was how Arthur Platt in the signal box at Knottewithought Junction alerted the staff at the station that a stopping train was about to arrive. This time it was the branch train from Wempole, terminating at Knottewithought.

Among the passengers was Mr Grimshaw. He used this service every day. Indeed, he travelled on every service, every day. Always in the window seat of the third compartment at the up end of the train. He faced the direction of travel towards Knottewithought, and had his back to the locomotive going up the valley of the River Knotte all the way to Wempole.

He was such a dedicated traveller that he never left the train, even when it was shunted into the sidings at the end of the day.

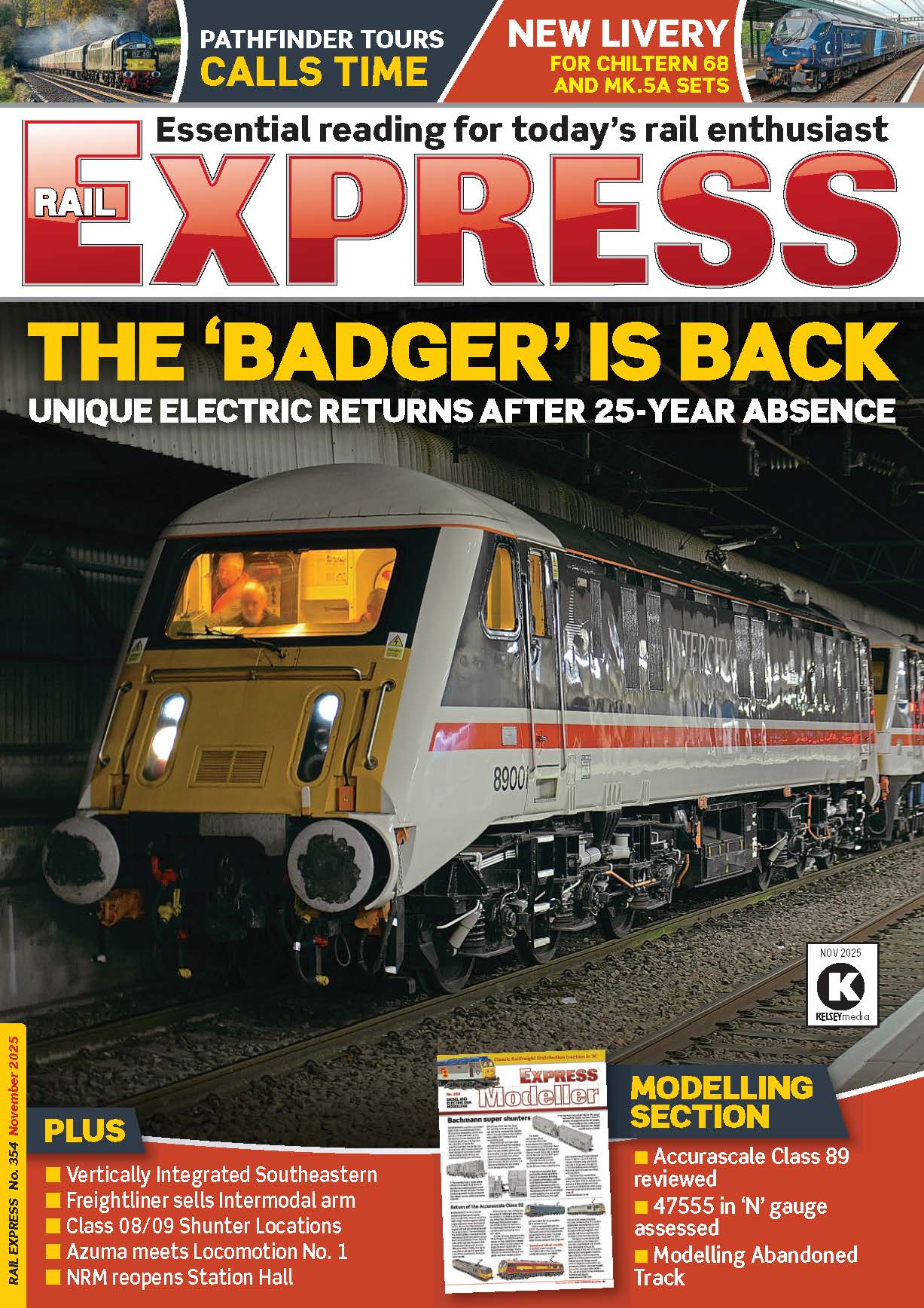

Enjoy more Rail Express Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

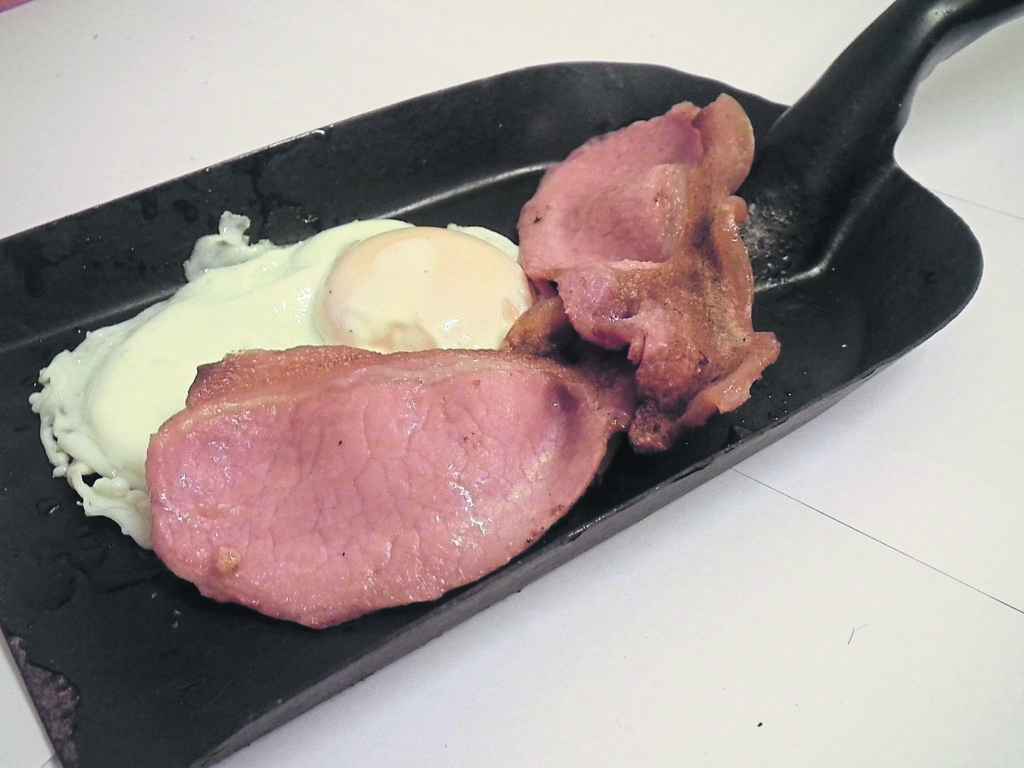

At stations, the guard would open the compartment door and invite Mr Grimshaw to alight, but he always declined. The driver would offer him mugs of tea, and the fireman would share his egg-and-bacon breakfasts. On the last train of the day Bill Carter, the porter, would give him leftover sandwiches from the station buffet. Mr Grimshaw remained a fixture on the train.

Then, one day, he wasn’t there. The guard, the driver, the fireman and the porter were most concerned.

They asked Albert Newton, the stationmaster, if he knew where Mr Grimshaw was.

Young Jimmy asked his Aunt Mary, as she knew everybody along the River Knotte, and nearly everything they got up to. Nobody had any idea what had happened to Mr Grimshaw.

It was on the mid-morning run to Wempole that the guard spotted Mr Grimshaw. He was sitting in the window seat of the third compartment, but at the Wempole end of the train, and on the other side of the train.

Then the guard realised that the entire rake of carriages had been turned end-for-end, and that Mr Grimshaw had moved with it. Even the locomotive was now chimney-first down the valley rather than bunker-first.

The guard couldn’t think how this might have happened as there was no triangle of lines at the terminus or at the junction, and the yard cranes were only of three tons capacity. Neither crane had turned a wheel, nor even lifted a load, in all the years he’d been working on the railway. It was a mystery.

Mr Grimshaw was delighted at the reversal. For the first time he could see the other side of the valley. He got completely new views of the River Knotte and its environs. He observed that when the river disappeared from view as it passed beneath the railway, it did not always reappear on the other side.

He noted that the heron never flew away as the train passed. He realised that Pott’s Bridge, a brick structure just outside Wempole station, had English bond on one side and Flemish bond on the other. He wondered at the reasons for these oddities.

But the reversal threw up two other oddities. At Knottethorpe Magna the middle carriage scraped along the lip of the platform, and at the sharp curve just outside Upper Knottewith Halt, the loco’s buffer beam only just missed the post of the speed restriction sign.

Such was the concern of the train crew that the stationmaster wrote a memo to the district superintendent about it.

And then, suddenly, the entire train was reversed. Mr Grimshaw was back to his customary position and the views it offered, and both carriage and buffer beam no longer had clearance problems.

Even though she was supposed to know everything that went on in the valley, not even Aunt Mary could explain how this might have happened.